The Pale Green Line

by Robert Gounley

Certain death. Small chance of success. What are we waiting for?Gimli, from the motion picture Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

On an early summer evening in Pasadena a large crowd gathered outside the main auditorium at Pasadena City College. On the other side of the solar system, a spacecraft approached the planet Saturn. The link between these two events was taking place at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. There, engineers and scientists huddled over computer monitors awaiting news from the Cassini spacecraft. The crowd had come to watch TV screens showing the JPL control room where Cassini was operated.

Seven years ago, NASA launched the Cassini spacecraft with an atmospheric probe, Huygens, built by the European Space Agency. Tonight this robot explorer would arrive at its destination. Once in orbit around Saturn, Cassini could begin a 4-year mission to explore the planet, its satellites, and rings. Huygens, released from its transport, will pass through the cloudtops and parachute down to the surface of the giant moon Titan, whose dense methane-rich atmosphere resembles Earth's billions of years ago.

|

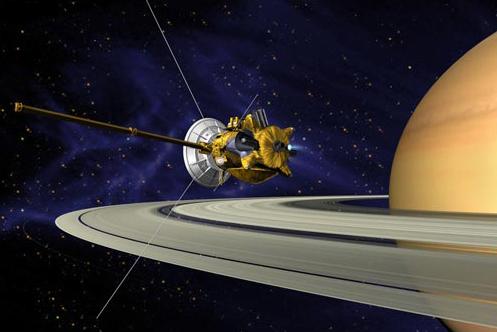

| Cassini during the Saturn Orbit Insertion (SOI) maneuver. NASA/JPL artist's conception. |

Great discoveries lay ahead. No spacecraft has visited Saturn since Voyager 2 flew by 23 years. It may be another generation before another returns.

Planetary scientists hope to learn much tonight, but Cassini's ultimate success depends on basic physics. One of the spacecraft's rocket engines must slow the schoolbus-sized spacecraft by the right amount and at the right place and at the right time—a Saturn Orbit Insertion (SOI). Miss the target and Cassini risks collision with boulder-sized ring material. Slow down too little and Cassini flies on past Saturn, never to return. Either way, the mission becomes a multi-billion dollar loss.

Tonight, Cassini's team at JPL can only watch their computer monitors, just as we were watching them. Radio signals take about 90 minutes to travel the distance between Saturn and Earth. When Earthbound observers see SOI beginning, the SOI maneuver at Saturn should be ending. The speed of light prevents ground controllers from any useful intervention as surely as an impassible road will keep fire-trucks from a mountain cabin before a blaze burns it to the ground.

Cassini must think and act for itself. The spacecraft was built with spare equipment ready to spring into play if ever a primary component fails in action. Onboard computers act as a command center, monitoring every step of the maneuver and applying sophisticated software to intercede wherever needed. It must properly respond to all potential problems, even when a failed sensor creates conflicting messages. Many JPL engineers spent years designing and testing this software. Tonight every one of them hoped it would never be used.

The auditorium filled with nervous spectators—engineers, scientists, and their families who could not be in the control room. Yesterday, I'd heard reports of high winds at JPL's tracking station in Australia. If the winds were too strong, all their antennas would be parked in their full upright position—never mind that a once-in-a-lifetime event was happening on the other side of the solar system. SOI's start can be monitored from antennas in California before Saturn set below the horizon, but only the Canberra station can keep Cassini in view for the entire burn.

To everyone's relief, the winds were dying down. Canberra would be on-line for the duration.

While we took our seats, the control room received word that Cassini had begun executing its first critical instructions of the evening. The control room at JPL and the crowd in Pasadena clapped and cheered as if their college football team had just put first points on the scoreboard.

Continued in the September 2004 edition of the Odyssey.

Copyright © 1998-2005 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.