Part 1 of The Pale Green Line appeared in the July 2004 Odyssey.

The Pale Green Line (part 2)

By Robert Gounley

Ordinarily, Cassini points with its large antenna dish facing the Earth. Now the spacecraft turned to point the antenna towards the rings. The best trajectory mission designers could find for SOI has Cassini passing through a gap between Saturn's F and G rings. If unseen dust filled this "gap", the antenna would the spacecraft from much of the buffeting. Until the maneuver was completed, Cassini's only communication would be through small omni-directional antennas. Signals sent this way are weak, but adequate to tell us where Cassini was and how fast it was going.

On screen, Todd Barber, Cassini's propulsion engineer kept a steady banter of color commentary. The radio signal remained steady. Cassini had crossed the ring plane and was still communication. The auditorium cheered this new milestone. On screen, Todd stroked his beard and smiled expectantly ñ soon Cassini's propulsion system would be the center of attention.

|

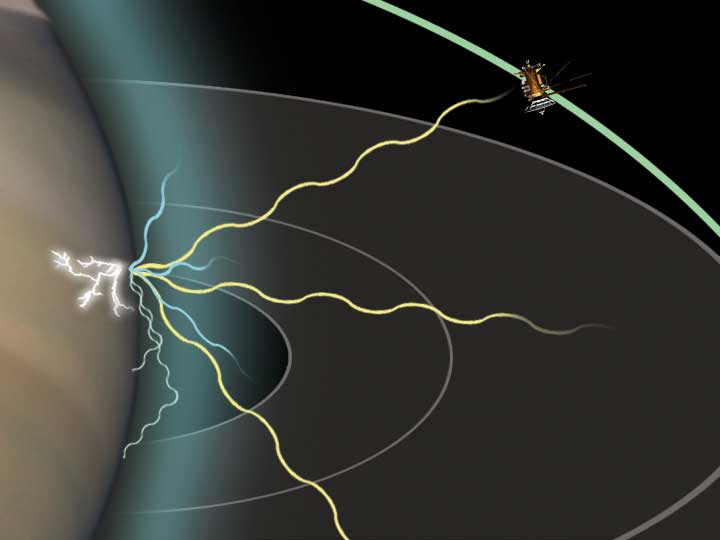

| Detecting lightning from Saturn. NASA/JPL artist's conception. |

The drama for the rest of the evening played out on a computer display projected into the auditorium. In pale green, a horizontal line began on the screen's upper left corner before suddenly tilting, like the top edge of a ski slope, down a diagonal trace before returning to horizontal at the lower right corner. This was the navigators' prediction of how, over time, Cassini's radio signal would change frequency (Doppler shift) as the spacecraft's velocity changed. The slope's crest marked the Doppler shift predicted for SOI's start; the base marked its end. Small undulations down the slope showed effects of Saturn's gravity and Cassini's curving trajectory.

One by one, tiny red dots appeared on the screen, advancing along the pale green line. These were the Doppler shifts measured by tracking stations on Earth. If the dots follow the green line, we'll know Cassini must be firing its rocket engine. If the red dots turn to horizontal too soon, Cassini will fall short of its required orbit.

At first, the dots scattered randomly in a band along the upper horizontal line. As viewed from the Earth, Cassini was behind Saturn's F-ring. Ring particles were scattering the signal. This noise, an annoyance to navigators and spectators alike, is information eagerly anticipated by radio scientists who infer from it the size and distribution of ring material. (In planetary science, one man's noise is another man's data.)

As Cassini's signal crossed into a ring gap and the dots began landing straight on the green line. At the predicted time, the dots turned downward along the green slope. Cassini's rocket engine had begun firing. (More cheers in the auditorium and control room.) Now we'd see if the dots would ride the ski slope down for the full 96 minutes required for SOI.

TV screens next the Doppler plot showed a NASA spokeswoman interviewing a succession of Cassini managers and scientists. The managers extolled the team who built and operated Cassini. The scientists elaborated on the scientific mysteries Cassini would unravel. In the auditorium, few listened. A hundred anxious conversations competed for attention. Occasionally, some in the crowd responded to something spoken in an interview. When a scientist responsible for the Cassini's Magnetometer appeared on screen, a few isolated cheers sprung from one of the front rows; everyone knew whom they were working for.

The new dots slowly marched single-file down the slope. When ring material intervened, the dots would break ranks and form a broad stripe centered on the green line. Sometime a few dots would fail to appear, suggesting obstruction by an especially dense ring layer.

The room hushed, as new dots appeared closer and closer to the horizontal line predicting SOI's completion. Hundreds of seats creaked as the crowd leaned forward. The red dots continued to the level of the horizontal green line -- and kept going. If others around me were sucking in their breaths, I could not hear them over my own.

On screen, the Cassini engineers looked a bit anxious as well. The silence was broken by a voice on the control room's intercom -- "Flight, Telecom. The Doppler has flattened out." Todd, beaming, provided his translation —"We have burn complete here!" SOI was nearly perfect. The suggestion of an overlong burn was actually a small misalignment in the display.

Everyone cheered, but the suspense was not over. The maneuver had been successful, but we still didn't know if the spacecraft needed to correct any problems during SOI. If that were the case, Cassini's computers would be rebooting into a quiescent mode when critical commanding were completed. The spacecraft would be safe, a full mission would be assured, but Cassini would stop collecting science data until the spacecraft team could sort out what happened and restart the sequence. (Think of recovering your work following a home computer crash.) The closest possible pictures of Saturn's rings require Cassini to be working smoothly now.

To give us an early sign, engineers had programmed Cassini to point its dish antenna back to the Earth minutes after the burn. It would stay there only a minute before turning to point its cameras at the rings (if the spacecraft had not gone into safe mode) or turning to a default safe attitude (if it had gone into safe mode). Initially, Cassini would still be transmitting through an omni-directional antenna. If Cassini were ready to gather ring data, it would signal by briefly switching to its dish antenna. We waited for Cassini to shout "I'm OK!"

Once more, the news was good. Cassini was healthy and ready to collect science data. More cheers. More hugs. A collective sigh of relief.

Next morning, Cassini's website was filled with pictures of Saturn's rings. They showed bands, braids, and even scallops. Scientists who waited a lifetime for these images talked as if they'd need the rest of their lives to explain them. Four years of new discoveries appear likely.

Over a billion kilometers away, Saturn has a new satellite.

Time to go exploring.

Copyright © 1998-2005 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.